Adoption Trauma – Part 1: What is Adoption Trauma?

A Note from the Author

As the Intake Director at Boston Post Adoption Resources, I have spoken to hundreds of adoptees of all ages who are reaching out for therapy, and I am grateful and honored that they have shared their stories with me. No two stories are alike, but all include adoption trauma, even if the adoptee is not able to name it when we first meet. I have also spoken with hundreds of adoptive parents, and I am often struck by their wish to better understand their child and how their early history and life experiences have affected them, so that they can give them the safest, most loving home possible.

To many, even the term “adoption trauma” may sound confusing. Often people think of adoption as a fully positive experience, a win-win for everyone involved. At BPAR, we acknowledge both the wins and the losses. Few of us stop to consider the earliest experiences that predate the adoption process and how the body and mind might record them as trauma. This is the first of a series of blogs that will address these issues and the challenges they may cause.

This first blog will explain the initial attachment disruption that occurs whenever a child and mother are separated. We will discuss early brain development and how a disruption impacts children of all ages, even if they were preverbal during the separation.

The second blog (coming in 2025) will reveal the ways adoption trauma might affect adoptees through all developmental phases and into adulthood, examine symptoms, behaviors, and triggers, and discuss the types of interventions, including therapy, that can support them on a path toward healing. In addition, we will share advice from adoptees to help adoptive parents address adoption trauma with their adopted children.

For these blogs, I have interviewed five adoptees, two adoptive parents, and three BPAR clinicians. Their voices will be heard throughout this series, and I am especially grateful for all of the time each of them spent with me openly sharing their stories.

At BPAR, we stress that adoption is a journey, and learning about adoption trauma and healing from it is also a journey. This is hard work, and it is especially important to pay attention to your own personal reactions as you read this article. Self-care looks different for everyone; remember to use the tools that work best for you as you process new information and make connections to your own life or the lives of loved ones.

—Erica Kramer, MSW, Director of Intake at BPAR

"For nine months, they heard the voice of the mother, registered the heartbeat, attuning with the biorhythms with the mother. The expectation is that it will continue. This is utterly broken for the adopted child. We don’t have sufficient appreciation for what happens to that infant and how to compensate for it."

—Gabor Maté, CM

Adoption Begins with Disruption

All of us have heard the prevailing narrative: once a child finds their adoptive home, they will have everything they need to live a happy life. But it is important to remember that every adoption story begins with an attachment disruption. Whether a child is adopted at birth or they are older at the time of adoption, their separation from the birth mother is a profound experience. The body processes this disruption as a trauma, which creates what may be called an “attachment wound.”

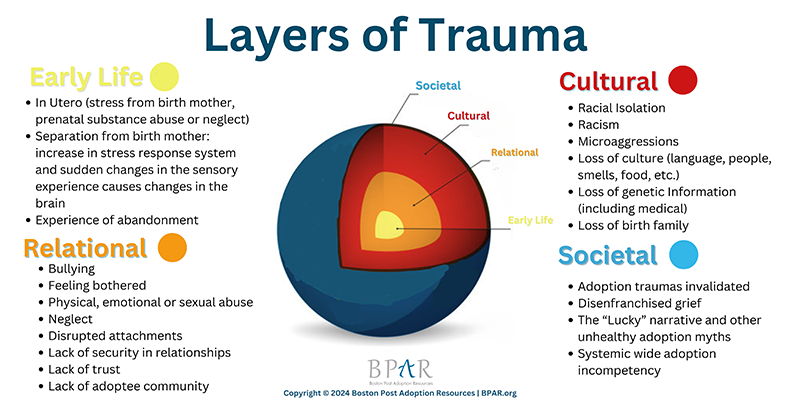

Nancy Newton Verrier declares that what she calls the “primal wound” is universal when mother and child are separated. "The loss of the child’s primordial loving, caring, and protective relationship can be indelibly imprinted on the unconscious mind as a traumatic injury" (Verrier, 1993). Beyond this initial disruption, a more nuanced understanding of the core issues of adoption teach us that adoption trauma may be very complex. Children often experience additional traumas, including racial isolation or abuse and neglect, and these are layered over the attachment trauma.

Research shows that early developmentally adverse experiences affect a child’s neurobiology and brain development. Researchers such as Bessel Van der Kolk and Dr. Bruce Perry stress that these early experiences impact the architecture of the brain. Marta Sierra, who is a BPAR clinician and identifies as a survivor of adoption, notes that preverbal and early childhood trauma during this crucial time of brain development is especially damaging.

Children need a secure attachment base. As attachment educator Paul Sunderland, a specialist in addiction counseling, has noted, "If you are given up at the beginning of life by the one person that you really need, where is the secure base?" (Sunderland, 2019). To understand the impact of adoption trauma on the adoptee, it is important to start by studying those early years, to understand attachment theory and explore how these experiences affect the brain.

Attachment Theory and How Separation Affects the Child

Adoption trauma begins with the initial separation from the biological parent. This separation can occur at birth or later in the child’s life, but it has an impact on the child no matter when it happens. Research shows that babies learn their mother’s characteristics in utero (Dolfi, 2022), including the mother’s voice, language, and sounds. For any infant, the separation from familiar sensory experiences from the in utero environment can overwhelm the nervous system at birth. BPAR clinician Darci Nelsen notes that if the first caregiver is not the birth mom, the newborn can feel frightened and overwhelmed, and this can cause them to release stress hormones. As BPAR clinician Lisa "LC" Coppola notes in her blog, "Adoptee Grief Is Real," (Coppola, 2023) "A baby removed from its birth mother's oxytocin loses the biological maternal source of soothing needed to relax the stress response system. Adoptees tend to develop hyper-vigilant stress response systems and have a greater chance of mental challenges."

The birth mother's emotional experience during the pregnancy can also impact the baby in utero. If the birth mother is experiencing stress, whether from homelessness or abuse or substance use, this can affect the growing baby. A mother who is feeling unable to care for their child and considering saying goodbye to their child is experiencing stress as well. When people are experiencing extreme stress, their bodies secrete cortisol and adrenaline, which in turn affects the growing fetus (Maté, 2021).

It's critical for the new mother to look at and hold their baby in order to soothe the baby’s stress response system. Breastfeeding is particularly beneficial. BPAR clinician LC Coppola notes that the interaction between baby and birth mother during the early days through breastfeeding and skin-to-skin contact is particularly beneficial and provides the anti-stress influence of the hormone and neurotransmitter oxytocin when the baby is born (Moberg and Prime, 2013).

After birth, the child's initial experiences with their caregiver have a profound effect on them. Attachment theory stresses that the baby-parent interaction teaches the baby how to regulate. Over consistent, daily repeated interactions between child and the caregiver, the baby begins to learn how to soothe and calm themselves. They slowly begin to associate relationships with trust and safety. If no one comes when a child screams and cries and fusses, the baby learns from a young age that their calls for help are futile. Although the baby might not understand words yet, they are particularly in tune to things such as tone of voice and other non-verbal cues from the adults. For example, if the baby’s needs lead to parent anger and frustration, they might learn to stay quiet.

A young child's attachment experiences may set up expectations and affect long-term behavior. When this early give-and-take regulation period is disrupted, the child can struggle with self-regulation issues as they grow. If they have been ignored or sense anger when they cry out for help, they may later seem overly independent because they learn that if they make no demands, this might keep them safer and caretakers more responsive. The effects, including expectations about future interpersonal relationships, can have a lifelong impact if these early beginnings aren’t explored and understood.

Nicole, a queer 30-year-old transracial adoptee who was adopted from China at less than two months old, was raised in a household of white adoptive relatives.

Understanding the Brain and Early Brain Development

“The experiences in the first years of life are disproportionately powerful in shaping how your brain organizes.”

—Bruce Perry, MD, PhD (2021, p. 31)

In order to understand how adoption and attachment trauma affects the developing child, it is important to learn more about the young brain. The majority of brain growth occurs in the first years of life.

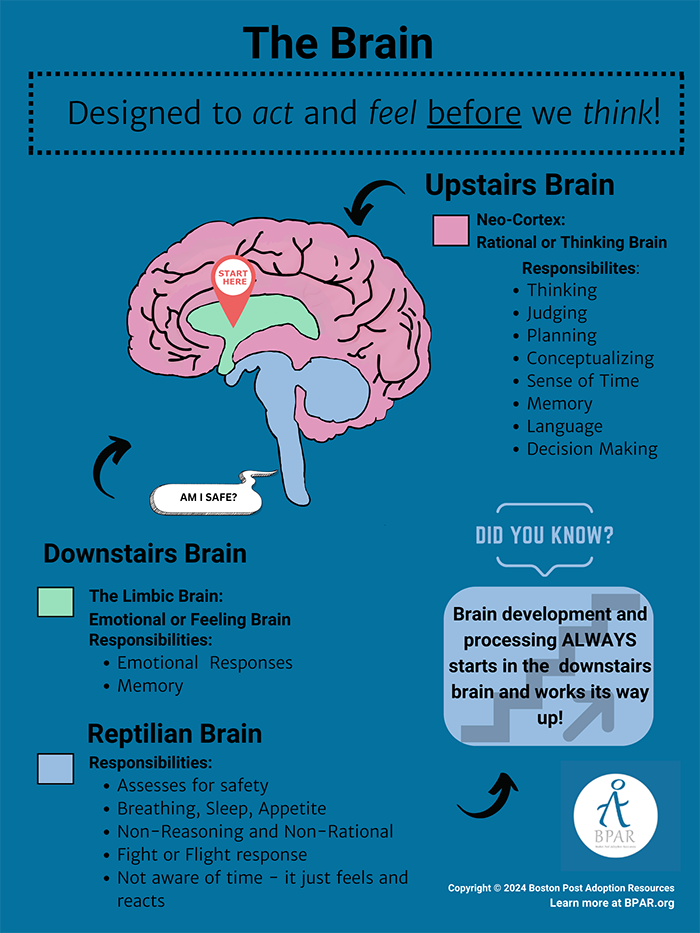

During the first year of life, the brain is growing rapidly and it is very sensitive to the environment. Keep in mind that the brain develops from the bottom up. Dr. Perry writes, "To get to the top, 'smart' part of our brain, we have to go through the lower, not-so-smart part. This sequential processing means that the most primitive, reactive part of our brain is the first part to interpret and act on the information coming from our senses. Bottom line: Our brain is organized to act and feel before we think" (Perry, 2021, p. 29).

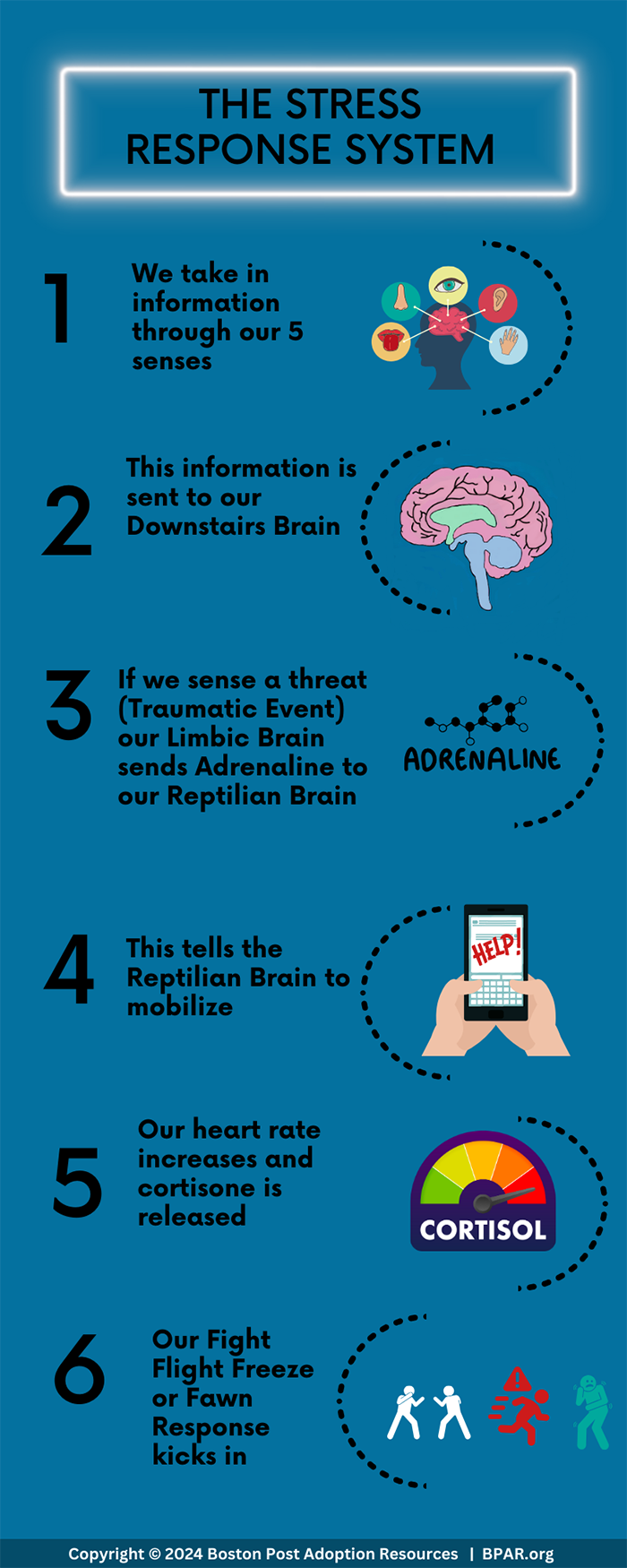

Any input from the outside world comes first into the lower areas of our brain, through the senses—vision, hearing, touch, and so on. A traumatic event—an event that the person perceives as unsafe—causes a shot of adrenaline and the limbic brain sends a message to the reptilian brain, telling it to mobilize. Our heart rate increases and stress hormones like cortisone are released. So in this way, anxiety is adaptive—it alerts us to potential danger by triggering a primitive neurobiological response in our brain. This triggers the survival response which most people have heard of—a fight/flight/freeze/fawn reaction. With young infants who of course can’t flee or fight, there might also be this tendency to retreat inward. The body slows down, the heart rate reduces and the body releases opioids as the child disengages and retreats. This is another adaptive strategy that can lead to dissociation, "disappearing" as a way to protect themselves.

Adoptee Development and the Brain's Response to Stress

Lisa and Olivia transracially adopted their daughter, who is now 20 years old, at birth. She was born in Hawaii and both of her birth parents are from the Marshall Islands. Prior to meeting their daughter, Lisa states that she and Olivia prepared for what it might be like for two white moms to adopt a baby of color and bring her to their home. "We understood that being adopted at birth was a huge deal for our baby. I remember holding her at birth and just looking at her and saying, ‘I know I don’t smell right, I know I don’t sound right. The person you really want is not with you, and I’m here for you.' I remember telling her that again and again. We were both really prepared to meet her in her grief. And that she was really in shock. . . . She was really shut down as a baby for the first several months, really inside herself. People thought she was a ‘good’ baby, but we were quite aware that our ‘good’ baby was really in shock and needed the time." Trying to ease their baby’s transition into their home, they stayed in Hawaii for two weeks, near the water so the ocean waves were close by, and engaged in a lot of skin to skin contact with her. They recorded the ocean so that when they moved to their home in the Midwest, their baby could still hear those familiar sounds. Olivia notes that years later, when their daughter was much older, she told her parents how hard it was for her when people would suggest that she should feel lucky that she is adopted. "My daughter felt, 'They think I should feel lucky, I should get over this thing, that my in utero experience didn’t matter.'" Lisa adds, "She was very traumatized and this was really hard on her. We are the ones who are lucky and we are all working very hard. We know our daughter is never going to ‘Get over it.’ That this is going to be a trauma response that will be part of her make-up and part of our family our entire lives."

Fast-forward to when the adoptee is an older child or an adult. Even if they are now in a safe environment, when something traumatic in the environment triggers the lower part of the brain, they might react as if the trauma is currently occurring. Remember, this is an instinctive response of extreme arousal in which the cortex cannot be accessed. Since the lower part of the brain cannot tell time, it reacts as if the original trauma is still happening. As Dr. Perry says, "What was once adaptive has become maladaptive" (Perry, 2021, p. 28). Without access to the more complex brain functions (logic, language, decision-making), people who have experienced early trauma take a longer time to regulate; they have stress-sensitive brains.

When Stress Turns Toxic

Keep in mind that in general, some stress is not a bad thing; with support, it teaches a child how to regulate their emotions and develop healthier ways to handle the inevitable stress that life brings. Studies show that a child’s reaction to a stressful event is mitigated if the child has a consistent, trusted adult to support them during the event.

In fact, experiencing difficulty and having the support of a safe adult is essential in helping children learn how to self-regulate and develop healthy stress response systems. Dr. Perry writes, "If the parent is consistent, predictable and nurturing, the stress-response systems become resilient. If the stress-response systems are activated in prolonged ways or chaotic ways, as in cases of abuse or neglect, they become sensitized and dysfunctional" (Perry, 2021, p. 58).

The type of stress that arises from toxic or unpredictable and chaotic early environments, however, can affect the child’s brain and early development. Toxic stress refers to chronic, frequent, or strong activation of the body’s stress management system (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, (2005/2014). The stress response system, for example, might learn to overreact. Even a very low level of stress might overproduce neural connections in the part of the brain that are involved with anxiety, impulsivity, and fear; at the same time, it might create fewer neural connections that are associated with reasoning and behavioral control. Signals are sent to the brain that trigger brain chemicals (including adrenaline and cortisol) and stress hormones, all of which cue the body to prepare for a threat.

Research has highlighted long-term effects of these heightened responses to stress (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2005/2014).

Implicit Memories Store Trauma in the Body

Implicit memories create a preverbal psychological wound that is remembered but not recalled. Because the child is so young, the body stores these memories in the limbic brain rather than the frontal cortex. Later the child might not recall early attachment disruption or trauma, but their body remembers them. As BPAR clinician Dr. Darci Nelsen notes, when the trauma occurs before we have developed language skills, memory is encoded through sensory and body-tactile experience because we don’t have the words to say what is happening. When the baby is not soothed, for example, their cortisol levels increase, and this process encodes the event into the nervous system.

Because trauma is stored in the body, it can impact nervous system development. The person will experience physiological triggers that they don’t have language for. Adoptees may be surprised when they are triggered by things in the environment that aren’t language-based but set off a pattern of dysregulation on a sensory level. And, as clinician Marta Sierra notes, because the trauma occurrence was preverbal, it can be triggered at any moment in their childhood or adult lives, and the person might not understand why.

In part 2 of BPAR's Adoption Trauma blog series, we will talk more about what happens when implicit memories are triggered for adoptees.

Adoptees Report Multiple Traumas

Separation from the birth family creates an attachment rupture that affects the adoptee in many ways. This initial trauma and the inherent loss and grief experienced by the adoptee often becomes layered with other traumas. These can arise from several moves and separations with multiple placements and numerous caregivers. Within institutionalized care, which is more common for international adoptees than domestic adoptees in the US, either inconsistent or strict schedules that do not target individual needs may be perceived as trauma. For a child who is adopted transracially and transculturally, moving to a new country can create an abrupt change in sensory experiences when they are suddenly surrounded by different smells, sounds, and language. With domestic adoptions, the child might experience multiple disruptions and caretakers within the foster care system.

Luz, age 52, was adopted transculturally and transracially from Bogota, Colombia. During her first year, she lived with her birth mother, who was a young domestic worker living with her employer. One day, her birth mother left her at her employer’s home and did not return. Luz was placed first in an orphanage and then with a missionary family and their three biological children. After a year, the mother died, and the father felt he could no longer care for Luz. She experienced yet another significant disruption when she was taken to Massachusetts where she was transracially adopted in a town with few people of color. She looked very different from her parents and her two siblings, who were the biological children of her adoptive parents.

Luz talks about the many attachment and separation traumas that she experienced in her initial years. Layered over these are other traumas. Central for Luz is that her adoptive parents did not acknowledge or celebrate her birth culture or her identity as a person of color

Grayson, age 29, speaks about the many challenges they struggled with while growing up as a transgender, bi-racial, transracial adoptee in a white family. Attending a predominantly white Catholic school was especially difficult for Grayson. "There was a lot of religious trauma. I thought that I would go to hell because I was queer." As a teen, they began using drugs and struggled with self-harm, leading to multiple hospitalizations.

Understanding Four Categories of Adoption Trauma

Naming adoption as trauma is a critical component of healing. BPAR clinician LC Coppola, an adoptee and author of our journal, Voices Unheard: A Reflective Journal for Adult Adoptees, acknowledges the many layers to adoption trauma, and she breaks these into four types of trauma.

1. Loss of Identity

The first trauma is the loss of identity. For the adoptee, this begins with the loss of their story, including any information about their ancestors and parents, and any genetic or biological history information. The term “genealogical bewilderment” is often used to describe the lack of birth family history that adoptees experience. It may be especially challenging for transracial adoptees who grow up in a home where their race is different from their family members and often their community members. When developing their own sense of identity, they see no one who mirrors them. We often hear from transracial adoptees how difficult it has been to live in a world where no one else shares their biology or looks like them.

2. Loss of Innate Trust

The second trauma for the adoptee is the loss of innate trust. This is the adoptee’s very first experience if they are separated at birth—the adoptee loses the sounds and smells of the birth mother—everything that is familiar to them—with no understanding of where she went. Whether the child is adopted at birth or later, there is a loss of trust, deep confusion, and an inability to articulate this. It is a feeling in the body, an experience of severing and abandonment. As mentioned already, that early separation impacts both brain development and the level of toxic stress in the young child’s body.

3. Loss of a Healthy Stress Response System

The third trauma that the adoptee experiences is the loss of a healthy stress response system. The initial separation, regardless of whether the baby was taken at birth or experienced other traumas later on, causes an immense amount of toxic stress early in life. For the young adoptee, there is no pre-trauma self to get back in touch with once they have some space from the trauma, no base to help them process the trauma and navigate the world again.

4. Disenfranchised Grief

The final piece of attachment trauma is disenfranchised grief. This refers to the lack of validation and support for the adoptee regarding their own personal history of loss and trauma. When a child has all these traumas as a first experience, often the people in their lives minimize their experience or do not acknowledge that these feelings can exist. The world around the adoptee presents this narrative that stresses how lucky they are and how grateful they should be. Everyone wants them to put a positive spin on it, and this does not allow for the acknowledgment of all that the adoptee has lost. This narrative does not give the adoptee permission to acknowledge and process their grief and loss.

David Drustruf, in his article, "The Hidden Impact of Adoption," notes that research has shown that society has often endorsed a narrative that adoption, like a "fairy tale," is a positive and "lucky" experience for all involved. He writes, "With the adoptee’s support systems engulfed in psychological and emotional struggles of their own, coupled with society’s misinformed perception of adoption, the adoptee can be implicitly encouraged towards silence and acquiescence. Herein lies the covert trauma of adoption—the lack of an outlet in which to wrestle with the grief and loss that are borne of the primal wound. Adoptees’ trauma is generally unacknowledged by society (National Adoption Information Clearinghouse [NAIC], 2004), and is complicated further by those three simple but problematic words, ‘You’re so lucky.’ Adoption remains the only trauma one is told he or she is lucky to have" (Drustruf, 2016, p. 3).

At BPAR, we feel every story like Gia’s, Nicole's, Luz's, and Grayson's deserves to be recognized. Understanding adoption trauma helps all those in the adoption constellation as well as friends and allies understand how to support adoptees and understand how their early histories might have affected them. Research supports how important this support and connection can be. In the second blog of this series, we will talk more about ways to support adoptees and their families, including developing healthy and safe coping strategies, and how to support all those in the adoption constellation who are on this journey. By educating the public about adoption trauma in this blog series, we hope to build more empathy so that one day, everyone in the adoption constellation feels understood, supported, and connected.

Written by Erica Kramer

Boston Post Adoption Resources

References

American Academy of Pediatrics (2016).Helping foster and adoptive families cope with trauma. https://downloads.aap.org/AAP/PDF/hfca_foster_trauma_guide.pdf

Coppola, L. (2023). Adoptee grief is real. Boston Post Adoption Resources Blog. https://bpar.org/adoptee-grief-is-real/

DiBenedetto, K. (2023). Why BPAR has to talk about the hard stuff in life after adoption. https://bpar.org/why-bpar-has-to-talk-about-the-hard-stuff-in-life-after-adoption/

Dolfi, M. (2022). Relinquishment trauma: The forgotten trauma. Marie Dolfi Blog. Retrieved from https://mariedolfi.com/adoption-resource/relinquishment-trauma-the-forgotten-trauma/

Drustrup, D. (2016). The hidden impact of adoption. The Family Institute at Northwestern University. https://www.family-institute.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/csi_drustrup_hidden_impact_of_adoption.pdf

Gabor, M. (2021). The trauma of relinquishment – Adoption, addiction and beyond. The Ollie Foundation. Retrieved fromhttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3CW_GdFG1KY

Moberg, K. and Prime, D. (2013). Oxytocin effects in mothers and infants during breastfeeding. Infant Journal, volume 9, issue 6. Retrieved from https://www.infantjournal.co.uk/pdf/inf_054_ers.pdf

National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. (2005/2014). Excessive stress disrupts the architecture of the

developing brain: Working paper 3. Updated edition. Retrieved from https://harvardcenter.wpenginepowered.com/wp-content/uploads/2005/05/Stress_Disrupts_Architecture_Developing_Brain-1.pdf

Perry, B. and Winfrey, O. (2021). What happened to you? Conversations on trauma, resilience, and healing. Flat Iron books.

Sierra, M. (2023). Attachment. Adoptees On Podcast Healing Series #237.

Sunderland, P. (2019). Relinquishment and adoption: Understanding the impact of an early psychological wound. International Conference Addiction Associated Disorders. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PX2Vm18TYwg

Van der Kolk, B. (2015). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Penguin Books.

Verrier, N. (1993). The primal wound. Gateway Press.