Search and Reunion — Voices in the Lifelong Journey of Adoption

Ilana is a biracial, 31-year-old transracial adoptee who was adopted at birth to white parents. When she was around eight years old, she began having seizures. She would wake up in the middle of the night with slurred speech and sometimes memory loss and think, “I must be dying!” She did not want to burden or upset her parents, so she decided not to tell them. One day when she fell asleep in her parents’ bed, they witnessed Ilana having a seizure and panicked. It turns out, the seizures were benign and easily treated with medication. It wasn’t until she was much older when Ilana began thinking about how she kept her seizures a secret for so long. She was trying to be the “good daughter,” the compliant child who always behaves. This is not uncommon for adoptees, who might worry that if they act out or cause problems, they will be sent away again. Taking this further, adopted children might not ask questions about their birth family for fear of upsetting their adoptive parents. As a child, Ilana was asked if she wanted information about her birth family, and she always said no. “My adoptive parents always felt I had a right to this information. It’s confusing that I never fully believed them. It is hard to ask a kid to make that decision. I didn’t really think I had a choice.”

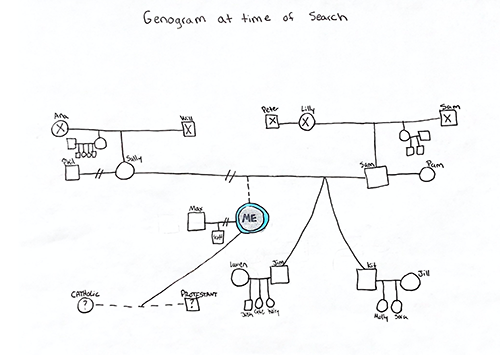

Sample genogram before search

Through my job as the intake coordinator at Boston Post Adoption Resources, I have spoken with hundreds of adoptees about their stories and struggles. For this blog, I interviewed in depth six adult adoptees who generously shared their search and reunion stories with me. I was continuously struck and honored that each of them shared so openly and thoughtfully their heartaches and challenges, as well as their triumphs. Most commented on how exhausting it was to tell their stories in such detail—an intense yet liberating experience for them. Pieces of their stories will be retold here.

How Adoptee Search Was Thwarted for Years

It is helpful to look at the history of adoption as a backdrop to understanding adoptee search and reunion. In the 1940s and 1950s, adoption records became closed.1 Secrecy was seen as a win/win: It helped the adoptive parent and child develop closer bonds, and it allowed the birth mother to avoid the stigma of being an unwed parent.2 Gabrielle Glaser writes, “Single motherhood, so commonplace today, was all but unimaginable in the 1950s and early 1960s. It inevitably was accompanied by ostracism, poverty, and unrelenting shame.”3 This was a time when abortion was illegal and contraception was forbidden.4

With the increase in two-working-parent families, teens and young adults were allowed more unsupervised time. This, of course, provided more opportunities for sex, with very little sex education and no birth control. The number of babies born to unwed mothers more than tripled between 1940 and 1966.5 By 1965, there were more than 200 maternity homes for unwed mothers in forty-four states.6 The number of couples wishing to adopt often greatly exceeded the number of babies; Glaser details standard practices at that time where young birth mothers were often not given information around the legalities of these adoptions, and in fact were often lied to; some were even told that their babies had died.7 “The Adoption Triangle Revisited,” a 2005 study by Triseliotis, Feast and Kyle, interviewed birth parents and adoptive parents of children adopted before 1975. 80% of the birth mothers felt pressured by either professionals or family members to make an adoption plan. 79% reported lasting guilt, and 98% stated that they thought about their child and wondered if they were happy.8 Slowly, starting in the 1970s, things began to shift as the adoptees’ rights movement began to take shape. After 1990, the rate of open adoptions slowly increased.

Genetic Testing and Other Ways to Search for Birth Family Members

Before the proliferation of genetic testing, the challenge of finding a birth family member often took years. Libby Copeland, in her 2020 book The Lost Family, notes that in 2017, DNA databases contained around 8 million people. Just 2 years later, in 2019 these listings soared to 30 million people.9 23andMe, one of the first DNA tests to be used recreationally, cost $999 in 2007; today genetic testing can cost as low as $99. By 2019, Copeland notes, most people could match with a relative sufficiently close in lineage to allow them to discover the identity of their biological parent. She adds, “It turns out, seeking is increasingly the easy part. It’s the finding that can be complicated.”10

Before the proliferation of genetic testing, the challenge of finding a birth family member often took years. Libby Copeland, in her 2020 book The Lost Family, notes that in 2017, DNA databases contained around 8 million people. Just 2 years later, in 2019 these listings soared to 30 million people.9 23andMe, one of the first DNA tests to be used recreationally, cost $999 in 2007; today genetic testing can cost as low as $99. By 2019, Copeland notes, most people could match with a relative sufficiently close in lineage to allow them to discover the identity of their biological parent. She adds, “It turns out, seeking is increasingly the easy part. It’s the finding that can be complicated.”10

Richard Hill writes about his search for his biological family in his 2017 memoir, Finding Family. Richard didn’t know he was adopted until his doctor revealed the truth around the time when he was graduating high school. Eventually, in 1981 he began to search for his birth family, a process that lasted until 2009. Along the way, he experienced many twists and turns and hit lots of dead ends. Richard used many techniques to try and find his biological family, including good old fashioned detective work as well the services of a search angel. He turned to DNA matching when it became available, and he is considered to be one of the first adoptees to ever use a DNA test to find his birth family. As the DNA tests became more sophisticated, they were able to compare people using more markers on the DNA strings, making more sophisticated matches. Richard writes, “The experts talk about nature versus nurture. Both are critically important in determining who we are. The inherent truth for adoptees, however, is that these two factors came from four different people. And many of us will never know peace until we know all the pieces.”11

Adoptees currently have many ways to search for their biological family. In addition to DNA tests and DNA registries, we are living in a world of social media. While both of these resources have in many ways increased the likelihood that adoptees will find family members, they have also added challenges and complexities to the search, as we have shared on our BPAR website. We receive many intake calls at BPAR where an adoptee tells us they took a DNA test and, although they were excited to learn about their ethnicity, they were not prepared for being matched with biological family members right away. The speed of these new connections can feel very overwhelming.

Brad, age 50, and his wife gave each other DNA tests for Christmas in 2016. They were curious about their ancestry, and although his wife’s family had told her a lot about her history, Brad’s parents were always very quiet about theirs. An only child, Brad believed he was the biological child of his parents. Two years later, Brad was contacted by someone who had matched with him as a relative; at first he thought she might be related to his mother, who he had just learned had been adopted. Slowly, Brad states, “things started to unravel.” It took him a long time to put things together. “When your reality has been one thing for so long, it’s hard to break down that wall.” Eventually he realized that he had been adopted. The person who had connected with him was his aunt, his birth mother’s sister. When Brad confronted his father, he acknowledged that Brad had been adopted at birth, “We’ve been trying to figure out how to tell you.” He reassured Brad that nothing had changed, “And I thought, this is bullshit—everything is different.” Learning that he was adopted, Brad says, was “a total unmooring. All the lines slip away, you lose all your identity at once. Some things are the same: my wife is the same, my kids, my job. But literally, everything is different.”

Why Do Adoptees Decide to Search for Birth Family?

Grace in Greece before adoption

People search for birth family members for a variety of reasons. As they grow and begin to grapple with developmentally appropriate questions about their identity, adoptees begin to wonder about their racial ethnic identity. They wonder what their first parents look like and why they decided to make an adoption plan. Adoptees might want answers to the many questions that have been swirling around in their heads and that have been difficult for them to articulate. All adoptees experience loss— loss of their birth parents, birth siblings, foster families, their birth culture, and possibly their birth country. A birth family search can provide a way to connect to these pieces of their past. Grace, a 30-year-old international adoptee from Greece and an only child in her adoptive family states, “I always wondered about my birth family. I always had an urge to find them.” When she was little, she used to fantasize each Christmas that her birth parents would appear at her front door on Christmas morning.

The urge to begin the search process can arise for a number of reasons. It does not necessarily imply that the adoptee wants a relationship with birth family members. Often significant life events trigger a search: the death of an adoptive parent, the birth of a first child, or the discovery of a new medical issue, to name a few. Rachel is 47 years old, adopted domestically at birth by white parents. She is bi-racial; her birth mother is white, and her birth father is black. Rachel did not think about a birth family search until she was an adult. “I was dating a guy who was Irish, and I began wondering about my ethnicity. I was more interested in my ethnicity, not in reaching out. I just wanted to know what I was.”

Dalit, age 61, was adopted domestically at a time when adoptions tended to be closed and secretive. She remembers how her identity questions began to surface when she was around 11 years old. “I started to feel like an alien, that I was sort of plopped down onto the earth with no connection to anyone.” As a teen, Dalit states, “I began to fantasize about finding someone who looked like me so I would have a kind of mirror. I was so unhappy, I struggled with depression, and although I’m not sure I was conscious of this, I fantasized about meeting a person who would understand me.”

Complexities of Search for Adoptive Parents

Grace as a baby

It is not uncommon for adoptees to wait until after an adoptive parent dies to search for birth family members. If they do search while their adoptive parent is alive, adoptees sometimes worry that their parents will become upset that they are searching. Grace comments that after her first trip to meet her birth family, “I could feel my mother’s anxiety. Before that, she was supportive, but then she was like, ‘What about me?’”

Research suggests that more openness about birth family leads to closer parent-child relationships. It is important to prepare adoptive parents for the possibility that, at some time in their lives, their child might decide to search for birth family members. This desire is natural and to be expected, and it is important to support their child and allow them control over the experience. Ilana stresses: “Adoptive parents need to feel secure enough to grapple with their child being theirs but also not theirs. A child is not a blank slate even if they are adopted at birth. The child needs to know that their parents can handle the complexity of adoption and identity.”

Susan Soonkeum Cox stresses the importance of preparing adoptive families with the knowledge that “search and reunion is a natural process that many adoptees will want to initiate at some point in their lives, and their role as parents is to be understanding and supportive.” The decision to search, she says, is one that should be made by the adoptee when they are developmentally old enough to make this decision. In Triseliotis’ study, many adoptees stated that, although they had questions, they felt uncomfortable talking to their parents, and they worried that asking questions might upset their parents.12

Some adoptive parents worry that their child will experience another rejection. Rachel told her parents as soon as she connected with her birth mother. “They were interested, they wanted to know everything. They are grateful to my birth mother. But my father was a little anxious—he wanted me to experience love and not rejection. They were fine as long as I was safe emotionally.” Dalit notes that her relationship with her adoptive parents is complicated, and she did not connect with her birth mother until after they had both died. She states, “There’s something about my parents being gone, it made me appreciate them even more. I wish I could go to them. I want to tell them that I found her and she’s not perfect. They are still so much my parents. I would like to tell them that my ability to bond has been damaged through relinquishment, but I appreciate their loyalty and constancy. There was never a question in their minds that I was their daughter.” Angela Tucker writes, “I’m glad that my family understands that my desire to search and learn more about my roots does not simultaneously end my desire to be a part of my [adoptive] family. Finding my birth family has never been an attempt to replace anyone else, but simply an effort to find myself.”

The Ups and Downs of Birth Family Search

Holy Cross Children's Home in India

At BPAR, we frame adoption as a lifelong journey. The decision to search for birth family might be part of that journey. Everyone has their own story, and this decision is unique to them. It is helpful for the adoptee to look at why they are searching so they can identify their expectations and fantasies and plan for the possibility that these expectations might not be met. For one thing, meeting birth family members won’t magically heal long-held feelings of trauma and loss. It might not even be possible to find those family members, or the process could hit lots of stumbling blocks that consume time, money, and energy. If adoptees do find a birth family member, they might learn truths that are difficult to hear, or the birth family might not be interested in contact. Grace explains that this is what held her back for a while. “My holdup was always secondary rejection. That was the biggest barrier.”

Many of the people I interviewed went through much trial and error as they searched for their birth family. Dalit searched for around 40 years, hitting many dead ends. Along the way, she learned that both of her birth parents were deaf, however, this piece of information did not make it easier for her to find them. She began, like Richard Hill, during a time preceding social media and DNA testing. Once she hired a man she found online who claimed to help with birth searches. He took her money, and she never heard from him again. In the 1990s, she contacted an organization called ALMA, founded in 1971. Gabrielle Glaser talks about ALMA in her book. Florence Fisher, an adoptee, founded ALMA (The Adoptees’ Liberty Movement Association) in New York in 1971 to help open adoption records and to develop a registry for adoptees and birth parents. The volunteers from this grassroots group have helped countless people find birth family members.13 Once Delaware finally opened up birth records, Dalit was able to get her birth certificate and learn her birth mother’s name. This discovery, however, led to many more dead ends, partially because, as often happens, her birth mother had married and changed her name. She did a DNA test, but had no matches.

After many ups and downs, Dalit felt that she was ready to stop searching. “Every time I made an attempt to search, it was like ripping off a scab. Then it would scab over again.” She attended BPAR’s 2019 Voices Unheard event and listened as adoptees told their stories by reading a piece of their creative work. “A few minutes into the event I started crying, and I wept for the entire evening. I guess I wasn’t done.” Although she had been in lots of therapy over the years, she had never worked with an adoption informed therapist until she connected with BPAR. Dalit states, “I don’t think it was clear in my mind that I would search, but I knew I wasn’t done and I still had a lot of grief and pain associated with being an adoptee.” As she began to come out of the fog, Dalit decided to resume her search.

Reunion Is Optional, and Only When You Are Ready

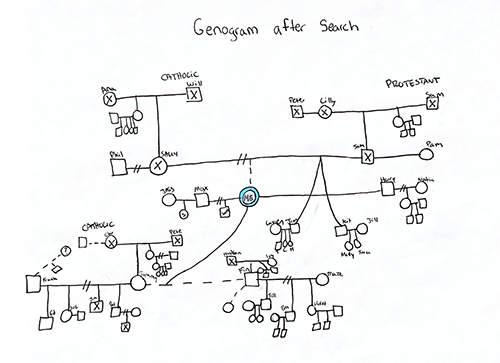

Sample genogram after search

Research suggests that many adoptees have had positive experiences with reunion. Triseliotis, et al (2005) report that 85% of the adoptees in their study reported that contact and reunion was positive. Most felt that it enhanced their sense of identity and helped them answer some of the questions they had. 50% of those who had felt previously rejected found that these feelings disappeared after the reunion. 97% said that meeting their birth parents did not change their feelings about their adoptive parents.14

If an adoptee chooses to make contact with a birth family member after a search, it is important to remember that this attempt to connect is a process, not an event. It can be negotiated and renegotiated over time as the relationship grows, shifts and changes. At BPAR, we frequently hear about adoptees who quickly found birth family members, but were not yet ready to meet them. Pacing after initial contact is important; it is okay to take your time. Ilana notes that her adoptive parents had told her the name of her birth mother several times, “But it never stuck. I would forget it over and over, until I was ready. I would go through weird periods where I would get sudden urges to Google search, but then I would forget her name.” Once, she met with a social worker who could facilitate birth family connection just to ask what it would be like if she did decide to search. Much later, after she found her family on Facebook, she waited a year before making any contact with them. “I didn’t know how to know when I was ready. I just needed to work on some things with my adoptive parents first, my feelings about hurting them. I’m holding this fear that I could destroy everything, I could really hurt them.”

32-year-old Marcos, adopted from Brazil at age 6 months, has completed a preliminary search for his birth mother, but he has chosen not to make contact yet. He reached out to the lawyer who organized his adoption, and the lawyer knew how to reach his birth mother. Though Marcos told this man that he was not yet ready to meet her, one day he received a voicemail (and two photos) telling him that his birth mother was in the lawyer’s office, available to speak with him. Marcos states, “I immediately stopped talking to him. I didn’t talk to him for three years. I had just wanted basic information about myself and to learn about my history. I didn’t know I wasn’t prepared, but I wasn’t. I wasn’t prepared for that level of connection. I needed to take a huge step back.” In individual and group therapy at BPAR, he has explored and grown and learned about himself. “I discovered in treatment that I have severe abandonment fears, a fear of losing people. In group I get to hear others who feel the same way. It was lonely, and it’s nice to hear others experiencing the same things.” In early December 2020, the lawyer again reached out to Marcos, sending him a baby picture and a holiday present. Marcos emailed back in late January to ask how his birth mother was doing, and to tell him that he is still not ready to talk with her. Marcos’ advice to others thinking about searching “is advice that I don’t always take myself. A part of me feels guilty the more time goes on, but you need to be kind to yourself. Allow yourself to take a breath. You need to listen to yourself and know it’s okay to take your time.” Marcos spoke about losing his adoptive father and the pain of knowing he will not be at his upcoming wedding. Speaking of his mother, he adds, “Adoption starts off with a loss. Part of the search and reunion journey is letting someone into your life who is actually your blood. At some point, I will have to accept that she will pass as well. There is a lot of fear around loss. You need to take the time to work these things out.”

Pacing and Boundaries Are Key to a Reunion

Careful pacing is just part of the equation. After a birth family member has been found, it is helpful to set up boundaries around contact, including phone calls, visits, and texts. 47-year-old Rachel connected with a cousin through DNA, and this led her to her birth mother. She states, “I was apprehensive about jumping in. We started with text and pictures, and then moved to conversation.” They promised to call weekly for a year, and then Rachel flew out to meet her for the first time. Rachel’s birth mother offered to let her to stay in her home. Rachel states, “I’m an extroverted introvert, and I need space. We rented an Airbnb nearby.” During this visit, she met several birth relatives, including her birth siblings. It helped to take breaks when she was feeling overwhelmed. Now they stay in contact, and Rachel observes, “I know my roots now in a way I didn’t before. I feel more grounded.”

Ilana’s reunion with her birth mother began just before the Covid pandemic hit. She states, “It has gone slowly, which is good for me. We started off with emails. [With] each step toward more intimacy, I think, ‘Uh oh, am I ready?’” Once Brad learned he was adopted, he felt he needed to carefully pace things with his aunt. He had her give information to his wife, and she “fed me pieces as I asked for them.” He learned that his mother had died many years ago, and his father was in prison. He learned that he has half-siblings. Slowly, Brad started to message his aunt through Messenger. “There was so much emotion, it was easier to do it on Messenger so I could read and digest, and I didn’t react right away.” When he felt ready, Brad eventually connected with his birth father and visited him in prison. Brad stresses how important pacing is: “Be super selfish. Let me do this at my own pace; my world has just turned upside down.”

Reunion Can Be Positive, Negative, and Everything In Between

Research suggests that most adoptees and birth family members report positive experiences with reunion. It has been found that meeting birth family members may enhance an adoptee’s sense of identity; they often report feeling more complete, and experience a decreased feeling of loss. Adoptees often describe meeting their birth family as the first time (if they don’t already have children of their own) that they saw someone who shares their genes and looks like them.

However, reunion brings complexities, and it is helpful to know what to expect in advance. Some adoptees must work through the fear of secondary rejection, and meeting birth family members can trigger old wounds and feelings. Dalit recently found her birth mother, and they have sent texts and had video chats, but they have not yet met in person. Dalit states, “I still have no sense of security that she’s not going to disappear. I’ve always been the one who leaves first. I have an escape hatch, always. How do I stay in this relationship?” Reunion can generate many highs, especially during the initial “honeymoon” period, but it can bring lows, as well. Dalit adds that it is important to remember that “This is not going to be a Hallmark moment. You will need to unpack a lifetime of feelings.”

Reunion can be equally complex for birth parents. Some birth mothers marry and have other children, but their families aren’t aware of the child they had relinquished. For instance, Grace, the 30-year-old adopted from Greece, explains that her extended family was told that she died at birth, and only a few close family members knew the truth. Sometimes birth fathers aren’t aware that they had a child. No matter what, integrating multiple family members can be very challenging.

International Search and Reunion Can Involve Added Challenges

Searching internationally adds more complexities to both the search and the reunion, partially due to cultural issues and language barriers.15 In addition, although this can also happen with domestic adoptions, it is often more likely that the information given to adoptive families at the time of an international birth is inaccurate. Grace asked the agency in the US that orchestrated her adoption to connect with the agency in Greece that placed her. Her parents were still living in the house where Grace’s birth father was born, and the agency was able to find them easily. However, after their initial contact when they exchanged some letters, there was a year of silence due to a misunderstanding. Grace believed that her birth parents needed time to tell her two siblings about her, both of whom were raised in their biological home. Her parents were waiting for Grace to initiate contact through the agency. After a year, Grace found her biological sister through Facebook. She had been told about Grace a month prior, and she was open to contact. Two years later, Grace visited her family in Greece, and she has visited almost every year since then. Grace acknowledges, “There is a lot to navigate. My older sister is the only one who speaks English, so there’s a huge language barrier. I have gotten a lot of answers, but there is still secrecy.” Grace adds, “I have realized I’ve always been a part of this family; of course we’re family. But it’s not my life, it’s not the life chosen for me. It’s a double-edged sword. I love life in America. I have so many opportunities. But Greece does feel like home.” When asked if she has any advice for adoptees who are considering a search, she states, “Make sure this is something you truly want to do, and be prepared for all the outcomes. Sometimes it hurts worse now because I do know them and I want to be there. Not all of your questions will be answered. You have to be okay with that.” Ultimately, Grace feels that meeting her birth family “helped me to understand my identity and to know my medical history.”

Maya at the Taj Mahal

Overseas there are programs in different countries to help with birth family search. There are times, however, when birth family members are not found. Some adoptees find that visiting their birth country and connecting with their birth culture helps build their cultural identity. Susan Soonkeum Cox notes, “It can help adoptees better understand and accept some of the nuances that come with working within another country and culture.” BPAR clinician Maya, adopted transracially from India, has visited India twice. She describes the first visit, when she was 7 years old, as a difficult experience. As a young child, she felt terrified that her adoptive parents were going to leave her at the orphanage in India, yet she was too afraid to ask them if that was the plan, fearing that their answer would be yes. Last year, as an adult, Maya returned to India. Although she has not been able to find birth family members, she described how powerful it was for her to make positive memories during this visit. She states, “I am now more open to talking about Indian culture, letting it be a part of me.” Maya visited the hospital where she was born and saw the delivery room. She also visited the orphanage. She has two pictures of herself from that time, one of a nun holding her. During her visit to the hospital, that same nun happened to be visiting for lunch, and Maya was able to meet her. “It felt surreal. I think it was magical—such a special thing. It’s sad that this connection is as close as I can get right now, but I think it can be enough right now.”

Adoptees Offer Advice on Asking for Support

Every person I interviewed for this blog spoke about how essential it is for an adoptee to have strong support in place once they decide to search for a birth family member. Grace was able to rely on a group of friends. She began her search before discovering BPAR. “I wish I’d had BPAR. It has been a very lonely experience for me. It was hard to meet people who understood.”

Rachel adds, “First, get a good sense of yourself. Get to know yourself well. Make sure you have a good therapist. There will be a lot of stuff to work out in your mind. I have learned to honor myself and my self-worth. My story is my story: This is me; I’m not broken. Hard things have happened to me that I had no control over.” Brad notes, “I don’t think there’s anybody alive that is fit to process this on their own.” Therapy is hard, Brad warns, but it is important to have support.

Many of the people I interviewed also attend groups with other adoptees. Marcos comments, “You feel less alone when you know there are other international adoptees. In a weird way, meeting with them every month is part of my search and reunion process.” He adds, “The way people I have been working with approached me, I feel accepted. I am working on feeling worthy and accepting compliments and not being so hard on myself. When I started at BPAR, it opened the floodgates—things I had not talked about in detail to anyone. I feel like a much better person now. I feel so much lighter.” Ilana adds, “I wish I had BPAR earlier. I needed that. Seeing the kids in the waiting room, I get a little jealous. I imagine if I was in a group with other adoptees when I was 10, or having an adoption-competent therapist.”

Many of the people I interviewed also attend groups with other adoptees. Marcos comments, “You feel less alone when you know there are other international adoptees. In a weird way, meeting with them every month is part of my search and reunion process.” He adds, “The way people I have been working with approached me, I feel accepted. I am working on feeling worthy and accepting compliments and not being so hard on myself. When I started at BPAR, it opened the floodgates—things I had not talked about in detail to anyone. I feel like a much better person now. I feel so much lighter.” Ilana adds, “I wish I had BPAR earlier. I needed that. Seeing the kids in the waiting room, I get a little jealous. I imagine if I was in a group with other adoptees when I was 10, or having an adoption-competent therapist.”

Ilana states, “There’s been so much grief throughout this process. I still feel it sometimes when I talk about it. I’ve learned not to fear the grief. It felt like I was going to jump off a cliff and I had no control. Once I realized I could survive this, I could move forward.”

Written by Erica Kramer, MSW

Boston Post Adoption Resources

Additional Search and Reunion Resources from BPAR

Blog Notes

1 Samuels, p. 2.

2 March 2015, p. 106.

3 Glaser 2021, p. 135.

4 Glaser, p.7.

5 Glaser, p. 39.

6 Glaser, p. 55.

7 Glaser, p. 139.

8 Triseliotis et. al.

9 Copeland, p. 5.

10 Copeland, p. 140.

11 Hill, p. 250.

12 Triseliotis et. al.

13 Glaser p. 191.

14 Triseliotis et. al.

15 Holt.

Blog References

Articles

“International Search and Reunion: A Conversation with Susan Soonkeum Cox,” Holt International (2015). Retrieved from https://adoptioncouncil.org/publications/adoption-advocate-no-90/.

Karen March, “Finding My Place: Birth Mothers Manage the Boundary Ambiguity of Adoption Reunion Contact,” Qualitative Sociology Review, (2015) 11 (3), 106-122.

Elizabeth Samuels, “How Adoption Grew Secret,” Adoptive Families. Retrieved from

https://www.adoptivefamilies.com/talking-about-adoption/closed-adoption-records/.

John Triseliotis, Julia Feast and Fiona Kyle, “The Adoption Triangle Revisited,” BAAF (2005). Retrieved from http://www.adoptionsearchreunion.org.uk/NR/rdonlyres/930CFE66-1B5E-44A9-9021-3C824EB0EF1F/6/finaladoptrianglesummary.pdf.

Angela Tucker, “Are Adoptees Selfish for Wanting to Search for Birth Parents?” Adoptive Families. Retrieved from https://www.adoptivefamilies.com/openness/adult-adoptees-considered-selfish-for-wanting-to-search-for-birth-parents/.

Books

Libby Copeland, The Lost Family. New York: Abrams Press, NY, 2020.

Gabrielle Glaser, American Baby: A Mother, A Child, and the Shadow History of Adoption. New York: Penguin Random House, 2021.

Richard Hill, Finding Family, Familius LLC, 2017.