The Masks We Wear

The golden light of autumn pales in the twilight, which softly creeps upon October afternoons. The rural byways of New England transform into a kaleidoscope of color. Leaves turn, preparing their trees for the raw chill of winter. Costumes and reverie ring supreme. Pumpkin spice can be found in everything from lattes to dental floss and the spirit of Halloween falls heavy and hard upon us.

The golden light of autumn pales in the twilight, which softly creeps upon October afternoons. The rural byways of New England transform into a kaleidoscope of color. Leaves turn, preparing their trees for the raw chill of winter. Costumes and reverie ring supreme. Pumpkin spice can be found in everything from lattes to dental floss and the spirit of Halloween falls heavy and hard upon us.

It is during these days, when the passing of summer’s vibrance morphs the landscape into a rich wash of yellow, red, and gold, that the notion of “Fear” is embraced and celebrated. Transition, transformation, loss, and fear are ideas we often dare not explore throughout most of our calendar year. Yet, for a few weeks in October, these become not only comfortable topics to ponder, but invite rituals embracing such themes to thrive.

For the adoptee, the observance of Halloween may carry a unique nuance. The adoptee can truly attest to the ever-present ghosts of transition, transformation, loss, and fear, characters recurrent in every adoption story. These elements form a motif with which the adoptee is all-too familiar, and often open discussion of such themes is discouraged or shamed in day-to-day conversation. However, Halloween opens the door for further exploration and through donning a costume (or sometimes, by removal of the everyday guise worn in ordinary life) we can, on this day of fantasy, somehow embrace a more authentic version of ourselves.

The mask has been a long favored accessory of the Halloween season. The adoptee may find that he or she wears a mask more often than not and metaphorically speaking, the mask may be just as much a part of one’s every day ensemble as a pair of socks. The face shown to the outside world is often only a snippet of the individual’s internal workings.

The creation of an “Inside-Outside Mask” may prove to be a truly cathartic experience for an adoptee. When a person is adopted, often there are huge chunks of their personal history which are unavailable. This is particularly true in cases of closed or international adoptions. Through the construction of the “Inside Out Mask,” the adoptee has the opportunity to explore the elements of fantasy that may fill the gaps in one’s personal history. Furthermore, the adoptee has the space to form a concrete visual depiction illustrating how they relate to the world, juxtaposed with how they internally process the more private chapters of their personal story.

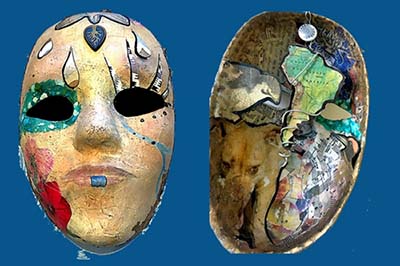

The “Inside-Out Mask,” is an exercise in examining how we present ourselves publicly as compared to the legitimate and real parts of self which, for whatever reason, we choose to keep private. The example shown herein, created by a 33 year old adoptee, depicts major discrepancies between what is shown to the outside world and what is left on the inside. The mask, originally a piece of smooth, unadorned, white plastic, takes on a new life. To start, the mask is covered, inside and out, with paper mache. This choice is deliberate, as layers and texture are integral parts of the artist’s story. For her, both the inside and outside of herself are a myriad of layers, waiting to be peeled away… some perhaps never to be revealed. The front of the mask was then painted a flesh tone indicative of Caucasian lineage… a deliberate and intentional aesthetic choice. Born in Colombia, adopted at 18 months, and raised in an Irish-Polish-Italian American family, this individual felt disconnected from her Hispanic heritage. The New Jersey suburb where she was raised was almost entirely white. Consequently, this woman experienced racism from a young age. Furthermore, her adoptive parents had described their trip to her native land as, “…a devastating exposure to poverty, armed military presence, and rampant drug trade in the streets.” They told their adopted daughter that she was “lucky” to have been brought out of the orphanage and into the States. Understandably, being “more white” quickly became a necessary survival technique. From a young age, the artist had internalized her Hispanic heritage as dirty, dangerous, and destitute. It was this white-washed version of self that she often showed to the world.

The “Inside-Out Mask,” is an exercise in examining how we present ourselves publicly as compared to the legitimate and real parts of self which, for whatever reason, we choose to keep private. The example shown herein, created by a 33 year old adoptee, depicts major discrepancies between what is shown to the outside world and what is left on the inside. The mask, originally a piece of smooth, unadorned, white plastic, takes on a new life. To start, the mask is covered, inside and out, with paper mache. This choice is deliberate, as layers and texture are integral parts of the artist’s story. For her, both the inside and outside of herself are a myriad of layers, waiting to be peeled away… some perhaps never to be revealed. The front of the mask was then painted a flesh tone indicative of Caucasian lineage… a deliberate and intentional aesthetic choice. Born in Colombia, adopted at 18 months, and raised in an Irish-Polish-Italian American family, this individual felt disconnected from her Hispanic heritage. The New Jersey suburb where she was raised was almost entirely white. Consequently, this woman experienced racism from a young age. Furthermore, her adoptive parents had described their trip to her native land as, “…a devastating exposure to poverty, armed military presence, and rampant drug trade in the streets.” They told their adopted daughter that she was “lucky” to have been brought out of the orphanage and into the States. Understandably, being “more white” quickly became a necessary survival technique. From a young age, the artist had internalized her Hispanic heritage as dirty, dangerous, and destitute. It was this white-washed version of self that she often showed to the world.

The outside of the mask also depicts the artist’s willingness to share her dedicated work ethic with the outside world. Cut paper in gold and silver represent beads of sweat, earned with grace, by a hardworking student. Hands and a bead with an upside down tree adorn the crown of the head, depicting the artist’s proclivity for meditation and desire for mental, psychological, and spiritual growth. All of these are elements that the artist wears on her sleeve, in her day-to-day interactions with friends, family, peers, and colleagues.

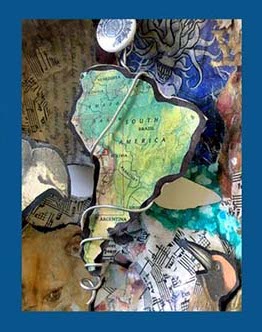

Upon flipping the piece over, a new world emerges. Suspended mid-mask is the continent of South America, tangled in wire. This is indicative of the inaccessibility of the artist’s native land. Colombia, for her, alway felt off limits and tremendous feelings of guilt would couple the artist’s attempts to research her native land. After all, if she was so lucky to have made it out of the orphanage, couldn’t she at least show her gratitude by not rooting around the dusty corners of a past long gone? The interior of the mask is lined with relevant journal pages and music scores, ripped and layered upon one another. They are painted over with sepia and take on the tone of old, faded wallpaper lining the interior of the brain-room. The image of a stray pitbull is deliberately selected and carefully placed. The pitbull, the most abandoned dog breed in the U.S., saunters out of the bottom corner, representing the artist’s fear of being misunderstood and subsequently abandoned. Two birds represent the birth parents, both of whom the adoptee has never met. Mother bird is on the right, looking stunned, vapid, and lost. Father bird leans in from the left, looking stern, unwelcoming and fierce. These birds represent the adoptee’s fantasy of whom her birth parents were and are present inside the mask despite the fact that in reality, these “birds” flew away a very long time ago.

Upon flipping the piece over, a new world emerges. Suspended mid-mask is the continent of South America, tangled in wire. This is indicative of the inaccessibility of the artist’s native land. Colombia, for her, alway felt off limits and tremendous feelings of guilt would couple the artist’s attempts to research her native land. After all, if she was so lucky to have made it out of the orphanage, couldn’t she at least show her gratitude by not rooting around the dusty corners of a past long gone? The interior of the mask is lined with relevant journal pages and music scores, ripped and layered upon one another. They are painted over with sepia and take on the tone of old, faded wallpaper lining the interior of the brain-room. The image of a stray pitbull is deliberately selected and carefully placed. The pitbull, the most abandoned dog breed in the U.S., saunters out of the bottom corner, representing the artist’s fear of being misunderstood and subsequently abandoned. Two birds represent the birth parents, both of whom the adoptee has never met. Mother bird is on the right, looking stunned, vapid, and lost. Father bird leans in from the left, looking stern, unwelcoming and fierce. These birds represent the adoptee’s fantasy of whom her birth parents were and are present inside the mask despite the fact that in reality, these “birds” flew away a very long time ago.

The Inside-Out Mask, for this adoptee, provides a creative process through which ideas of identity can be explored and expressed. Examination of the finished work proved revealing and the adoptee was able to look, with some objectivity, at the sundry of components that made her unique. Fears of abandonment and a lack of identity could be examined through texture, shape, imagery, and color. The artist is able to simply look at “fear,” and ask herself, “How dare I let fear play a part in my decision making, in my relationships, in my livelihood? I would be able to avoid this… if I were more open about my fear.”

As autumn rolls on, the days get shorter, and we prepare to dress up in costume and celebrate “Fear” on All-Hallows Eve, let us all remember to reflect on the masks that we wear. Our mask may be a way to hide from the world but maybe, our mask can transform into a means of sharing with the outside world, what our inside world is like.

Written by Caitlin Woodstock, Intern

Boston Post Adoption Resources