Remembering My Dads As I Hold My Boys

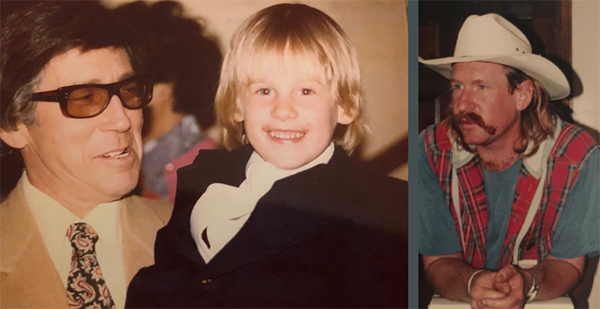

Stu, me, and Mike

I’ve seen two dead bodies in my life, and they were both my father.

Maybe that sounds like a riddle. Or like a story with a hole at the center. But adoption, you see, is complicated. Because for adopted people there is a hole at the center of our story. One that we can spend our lives never naming, acknowledging or understanding.

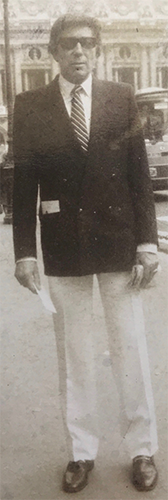

Stu, my adoptive dad

When my adoptive dad died, it felt like a pillar holding up the whole world had crumbled. He was 90, and despite his leukemia diagnosis, a child-like part of me was certain he would live forever. But less than three months after the diagnosis he passed away at our house, in my old bedroom. Watching him take his last breath, in a rented hospital bed, amongst the remnants of my teens and early 20s, I remember thinking that he no longer looked like himself. He looked alien. Like a stranger. This moment of alienation was, I think, an echo of something that had reverberated throughout our shared history; a ghost haunting the room. Though we loved each other, so often our relationship felt like trying to tune into a radio station, but never quite finding the signal. My former room, still crammed with old books, photos, tapes, CDs, posters, and trophies, was a litany of all the ways in which I knew was alien to him. An evidence locker of all the ways we didn’t connect. Sometimes I felt guilty about this, as if the lack of recognition or attunement was my fault. And then I would feel ashamed about the son that I was to him. With his final breath, I felt the chance to ever find the signal, to be recognized, to be a better son, evaporate.

Five years later, my first father died. He was 58, we were only 18 months into our reunion, and his death was a shock. At the hospital, my siblings and I each took a few private moments in his room, where his body was still resting in bed. Alone, I remember looking at him as if for the first time. As if I finally had permission. I looked at his body, just barely cold, and saw that he was me. I was of him. My adoptive dad loved me, but I wasn’t of him. His hands weren’t my hands, his eyes my eyes, the tint of his skin, the freckles on his arms, the hair on his chest. I hugged my first father’s body and felt not only the grief of losing him so soon, but also the grief of losing this freshly discovered recognition. The evidence that I came from somewhere, that I was connected to someone by blood and bone, was lost almost in the same moment I had discovered it.

As I try to solve the riddle posed by adoption, I sometimes see these two scenes as holding the key.

Stu, my adoptive dad, was a gentleman from an earlier era. He was already 55 years old when I was born in 1974. A Russian Jew from New York. Thin, long limbed, olive skinned. Genteel and genial. Quick with a smile and an often-corny joke. He sold commercial insurance, went to the office everyday, impeccably dressed in a suit and tie. I always assumed I should be able to do that. But between the ages 19-24 I had so many office temp jobs that I both hated and was terrible at. It made me feel ashamed sometimes, like something was wrong with me. Stu never judged me. But his way of being, so different than my own, was at times for me its own unspoken rebuke.

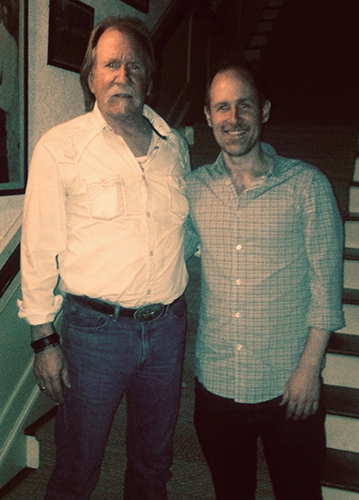

Me with Mike, my first father

Mike, my first father, was 18 when I was born. A Northern California farm country guy of the 70s. Hulk Hogan in cowboy boots and pearl snaps. Full of machismo and swagger. But he was also a creative free spirit. A talented winemaker. A painter. We reunited in 2014 and after only a few hours together, I finally understood what kind of man I was, better than I ever had. His version of a traditional masculine exterior that belied his more aesthetically refined internal life immediately made sense to me. I was an athlete through college, but my internal emotional and intellectual life often felt out of step with many of the male spaces I occupied. I was always slightly unsettled by this; it felt like I had something to hide. But after a night with Mike I felt more grounded in who I was. My internal life, some of how I walked in the world, my way of being, was reflected back to me in him.

At our first dinner, after swaggering by a table of women and stopping to flirt, he mentioned that he had once considered moving to Tuscany because he loved the movie “Stealing Beauty.” This obscure, 90s art house movie had sparked a similar longing in me when I saw it. His casual admission was startling. Stu, for all his love and gifts, had literally never plucked something out of my heart like that. That was the first time I felt like I had finally found the radio signal. It was like looking into a mirror for the first time and seeing yourself reflected.

The tragedy is that I was already 40. It had already been a lifetime. I wish that I’d started all this earlier so that I could reckon with the man I was and the son I might have been to both of my dads. Because to actually see myself reflected meant that I could finally see that I was a specific kind of man. I didn’t have to feel guilty or ashamed that I couldn’t be like Stu. It wasn’t a failing; I wasn’t inept. We just came from different places. And that was okay. But pretending that we didn’t, pretending that we could be alike, pretending that I could look to him for a clue about who I was, was the root of my shame and guilt. The silver lining, I hope, is that I started this reckoning right as I became a father.

My two sons are half Asian. They don’t have my eyes, or my hair, or my skin color. I have to look more closely to see myself in them. And without Mike, I don’t know if I’d be able to really see them. Without recognizing myself in him, I wouldn’t be able to recognize myself in them. My oldest son—creative, free spirited, quick thinking, strong willed, extroverted—is squarely within the male line of our family. It is a gift for both of us that I can see this and share that with him. My boys never got to meet their grandads. But we talk about them in our house. They know both Grandpa Stu and Grandpa Mike. They’ve seen pictures and videos; they’ve heard stories. This, in some ways, feels like filling in the hole.

Ultimately the challenge for every adoptee who becomes a parent is to not pass on the hole in our stories to our children. Because the hole in our stories easily becomes the hole in our hearts. And the hole in our heart manifests as emptiness and distance; as fears of attachment and vulnerability; as alienation and identity confusion. It can make us needy and, sometimes simultaneously, distant. We pull people close, then push them away. As a father I try to recognize where I protect myself, when I’m withholding love or affection, where my walls and defenses aren’t allowing my boys in. And I try to do better. I try to see them. To make them feel like they are seen and mirrored or that they’re finding the signal. That we are bridging the gap.

Sometimes, honestly, I’m faking it. Sometimes I feel a distance. I feel alienated. Or hurt, or emotionally abandoned, or afraid of being abandoned or emotionally rejected. But one day, when they are standing over my body, I don’t want them to feel guilt or confusion or shame about the sons they should have been or the men they might have become. I hope that they never have that kind of riddle to solve or hole to fill.

On Father’s Day I remember my dads. I hold my boys. I grieve the man I might have been, and try to imagine the man I can still become. And I also try, as best I can, to give a little bit of grace to the man, son, and father I am now.

Written by Derek Frank

Guest Writer

BPAR is grateful to Derek Frank for writing this powerful blog in honor of Father’s Day. Adoption IS complicated, and we are honored to give guest writers a forum for exploring the holes in their personal stories and sharing their voices on BPAR.org.