The Many Identities of Me: Coming to Terms with My Identity as a Transracial Adoptee

When a form asks me to indicate my race or ethnicity, I automatically select “Asian.” It is the race I see reflected in the mirror. It is the race that I present when walking down the street. To the world I am a 5-foot Chinese girl with a K-Pop-inspired hairstyle and a love of platform sneakers. But what the world does not see are the many identities swirling around in my head.

When a form asks me to indicate my race or ethnicity, I automatically select “Asian.” It is the race I see reflected in the mirror. It is the race that I present when walking down the street. To the world I am a 5-foot Chinese girl with a K-Pop-inspired hairstyle and a love of platform sneakers. But what the world does not see are the many identities swirling around in my head.

A psychologist’s definition of identity goes something like this: an individual’s sense of self defined by a set of physical, psychological, and interpersonal characteristics and a range of affiliations and social roles. Identity typically involves a sense of continuity, meaning it remains relatively unchanged day-to-day, despite any physical or circumstantial changes.

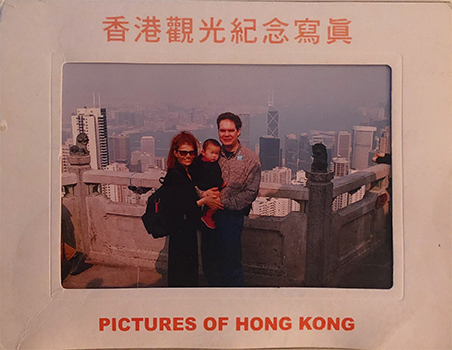

I have always identified as a daughter, dancer, and student: I am the daughter of two loving and supportive parents; I have been a ballerina since the age of 2; and though I recently graduated from college, I continue to see myself as a student on a gap year before attending graduate school. These were the three identities that defined me from childhood to adolescence. In retrospect, I clung to these identities as they provided me with a stable sense of self. However, there is another aspect of my identity I have either consciously or unconsciously ignored for most of my life: the fact that I am a Chinese, transracial adoptee.

My parents have always tried their best to keep me connected to my East Asian heritage. We tried to make dumplings for the Lunar New Year. We attempted learning how to use chopsticks (I unfortunately am the only one who succeeded). I have a small library of books exploring the Asian and Asian American experience curated over the years by my mom. I participated in Chinese Dance to supplement my ballet training for a year. As a seven-years-old, I joined the Mei Mei Jie Jie program at Wellesley College, a program designed to connect young East Asian adoptees to their college students of East Asian descent. But, despite my parents best efforts, I rarely fell in love with these activities. I was too ingrained in the ballet culture to want to embrace a new form of dance. I tended to be quiet and reserved in large group settings, so I struggled to connect with the other Chinese adoptees enrolled in these programs. This lack of interest only grew as I became a pre-teen and adolescent, when I began to truly resist my parents’ efforts to engage me with my Chinese identity.

My parents have always tried their best to keep me connected to my East Asian heritage. We tried to make dumplings for the Lunar New Year. We attempted learning how to use chopsticks (I unfortunately am the only one who succeeded). I have a small library of books exploring the Asian and Asian American experience curated over the years by my mom. I participated in Chinese Dance to supplement my ballet training for a year. As a seven-years-old, I joined the Mei Mei Jie Jie program at Wellesley College, a program designed to connect young East Asian adoptees to their college students of East Asian descent. But, despite my parents best efforts, I rarely fell in love with these activities. I was too ingrained in the ballet culture to want to embrace a new form of dance. I tended to be quiet and reserved in large group settings, so I struggled to connect with the other Chinese adoptees enrolled in these programs. This lack of interest only grew as I became a pre-teen and adolescent, when I began to truly resist my parents’ efforts to engage me with my Chinese identity.

Middle school marked a turning point for me. Despite forming friendships with a majority of the East Asian American students in my classes, I began to reject opportunities that could have connected me to my Chinese identity. This rejection was neither explicit nor conscious, but rather stemmed from a lack of genuine interest. Looking back, I think on some level I could sense that even my Asian American friends were going through a similar phase in their lives, too. Like many 12- and 13-year-olds, I think we were all trying to carve out a unique identity for ourselves while simultaneously trying not to stand out. We wanted to be cool, but we did not want to be the “nerdy Asian” or “weird” kid. As a result, we all had a tendency to downplay the things that might have made us stand out, the things that made us Asian. For me, this meant I fully embraced my culturally Italian upbringing, knowing that this identity would make me unique but not too “out there” for the predominantly white community I grew up in. I proudly explained how my family celebrated Christmas Eve with la vigilia (the feast of the seven fishes). I confidently proclaimed the magic of parmesan cheese and how it went with everything.

By high school, I started to lean heavily on my identity as a ballet dancer, too. If I was not at school or at home, there was a good chance you could find me in the dance studio. I also joined the nerdy but cool crowd with my love of Marvel, SuperWhoLock, Lord of the Rings, and musical theatre. I was finding my “thing,” or things as it were.

Back then, I would have told you I was secure in my identity and that I was not lacking anything. It is only now that I realize there was still something missing: any kind of acknowledgement or connection to my Chinese culture.

All this changed the day I moved into my First Year college dorm. I suddenly found myself surrounded by the richly diverse student body that made up my small, liberal arts women’s college. It was my first time experiencing what it was like to consistently not be the only person of color or the only Asian in the room. I met domestic and international students of Asian descent who identified with cultures from all over the continent. Seeing their varying levels of love and interest in their own unique and oftentimes multicultural backgrounds gave me the validation and confidence to explore my own Asian and Chineseness.

All this changed the day I moved into my First Year college dorm. I suddenly found myself surrounded by the richly diverse student body that made up my small, liberal arts women’s college. It was my first time experiencing what it was like to consistently not be the only person of color or the only Asian in the room. I met domestic and international students of Asian descent who identified with cultures from all over the continent. Seeing their varying levels of love and interest in their own unique and oftentimes multicultural backgrounds gave me the validation and confidence to explore my own Asian and Chineseness.

From that day on, I decided to learn all that I could about my Chinese culture. I made it my mission to make up for all the Asian food I had missed out on. I bought overpriced bubble tea, went on unnecessary visits to H-Mart, and made the hour-long journey for hotpot. I was even given the honour of charring the first piece of samgyeopsal (pork belly) when my Thai Japanese American roommate and I tried Korean barbeque for the first time. I watched my first anime and first kdrama. I went to the cinema to watch my first major, mainstream film to star an all-Asian cast (if you have not watched Crazy Rich Asians yet, I highly recommend it).

Those four years gave me the space to comfortably explore my Chinese identity at my own pace. It was a liberating experience. I finally allowed myself the opportunity to explore a side of me I had, at best, ignored or, at worst, saw as “uncool” or something to forget. (Yes, I distinctly remember the first time I realized I would sometimes “forget” I was Asian).

The sudden departure of students from campuses across the country and switch to remote learning in March 2020 left me shaken. I had finally found a safe space to not only learn but to grow as a person. I hurriedly packed up my dorm room with tears in my eyes. I found myself crying on the shoulders of friends who had supported me through all of this self-exploration, not knowing when I would see them in person again.

I ultimately departed campus with too many posters of Korean pop idols and a love of Korean dramas. K-pop and K-dramas opened my eyes to a world where people who looked like me could become singers, dancers, and rappers. I had become and continue to be fascinated and inspired by the industry’s international idols, hailing not only from Korea, but from China, Hong Kong, Japan, Thailand, the US, Canada, and Australia, as well.

Nearly a year after moving back home, I am continuing to embrace East Asian culture. I began watching Chinese dramas. I am once again trying to learn Mandarin. I started to share my Chinese birth name with pride, rather than embarrassment. I have introduced my white parents to some of the best ramen and look forward to the day when I can safely take them to hotpot.

Now, this is not to say I have completely come to terms with my identity as a Chinese, transracial adoptee. I am only at the beginning of that journey. I am still grappling with the fact that I was raised in a White environment and therefore missed out on significant parts of the Asian and Asian American experience. I still suffer bouts of imposter syndrome when I am with my Chinese and Chinese American friends. I may have been born in China, but I am still not Chinese in the same way they are, despite many of them being born in the States. On the flip side, I continue to wonder what people think when they see me, a Chinese person, walking down the street with my Italian mother and Irish American father. I have no way of knowing what people will think when they read the most Italian, Irish name on paper, but then a Chinese girl like me walks into the room. I am certain I will continue to struggle with my identity in the years to come, but I will try my best to give myself the space to do so.

Looking forward, I suspect 2021 will continue to be a time for self-reflection and exploration. I will continue having tough, in-depth conversations with my parents about all of the experiences outlined here. I hope to further engage in the online adoptee communities I joined in 2020. I eventually see myself studying the adoptee experience through the lens of a researcher, allowing me to better understand the psychological process at work. Only time will tell where I go from here, but I am excited to see what the future holds.

Looking forward, I suspect 2021 will continue to be a time for self-reflection and exploration. I will continue having tough, in-depth conversations with my parents about all of the experiences outlined here. I hope to further engage in the online adoptee communities I joined in 2020. I eventually see myself studying the adoptee experience through the lens of a researcher, allowing me to better understand the psychological process at work. Only time will tell where I go from here, but I am excited to see what the future holds.

By Marisa Nardone Mahoney (黄杨辉)

Guest Writer, transracial adoptee