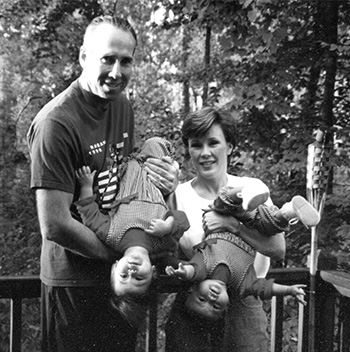

Learning to Be Different – My Transracial Adoption Story

Left to right: Diana, Alex, Veronica, John

People often ask me how old I was when I knew I was adopted, and I laugh as I spell out that it’s not really something you can hide in transracial adoption. From the moment that my sister and I could speak, our parents explained to us that we were adopted, and that this part of our own stories which made us different, also made us special; different didn’t have to mean strange or unwelcome. We always knew that our parents were Caucasian American and that they adopted me from Vladivostok, Russia (though I have an odd mixture of East-Asian heritage) and my younger sister, Veronica, from Yichun in the Jiangxi province of China.

Left to right: John (father), Alex, Diana (mother), Veronica (sister)

Some of my earliest memories are of my family celebrating Lunar New Year by decorating lanterns or learning the process of making Russian Fabergé eggs. For show-and-tell, I got to bring in nesting dolls or special trinkets that my parents brought back from Russia when they adopted me, and I was so proud to have a unique heritage. When children would ask me why my eyes are so “squinty” or why my parents don’t look like me, my parents always knew how to help me work through it and see how, more often than not, different is a good thing. In our house, there was always a positive association between where we came from and who we are.

As we got older and moved through adolescence, though I always understood that my cultural origins were different from those of most other people around me, I still never saw myself as racially different. Sometimes I think that this is because children don’t see race the same way adults do. However, most often I come to the conclusion that I didn’t see that I was a racial minority because I had subconsciously and consciously erased the “race” part of my cultural identity that had always made me feel different in the strange and unwelcome definition of the word. The universal adolescent urge to fit in coupled with a racially homogeneous social environment caused me to refuse to acknowledge that I was different altogether. People would say to me, “Oh, you’re not a real Asian though,” because my parents were white or because they perceived my social performance to be “not Asian enough” to fit their concept of what it meant to be Asian. Meanwhile, I had absolutely no concept of what it meant to be Asian because I had no model.

I felt like everyone was trying to put me in a box of being the one Asian girl in the grade, and I felt ashamed to be Asian. I began to reject certain elements of or related to Asian culture like anime series or select video games. I didn’t even wear my hair up in a high bun because I thought it looked “too Asian.” No one ever told me this, but I concocted this idea that it was better to neglect the Asian part of me so that I could fit in the box with everyone else.

Diana, Alex and John

These are the moments when I wish I could remind my past self that being different is never something of which we should be ashamed, and when we feel different, we don’t have to choose between suppressing that part of us or being isolated if we don’t suppress it. Any feeling of shame we have about our own identity doesn’t reflect poorly on us, but rather derives from others who try to place restrictions on who we can be.

I learned this lesson in college when I found myself on an extremely racially diverse campus with a large Asian-American population, many of whom grew up in predominantly white areas, too. I was finally able to see Asian culture modeled fearlessly with pride. What had previously made us weird or unwelcome to other kids now brought us together.

This was a crossroads in my life where embracing my cultural identity as Asian-American was my choice, and it was one that would be fully supported by all those around me. My parents had encouraged me to embrace my cultural heritage throughout my life, but throughout my childhood, going on that journey on my own felt impossible. In college I felt free to incorporate elements of Asian culture into my life, especially through cooking and fashion. I didn’t grow up with my parents cooking any type of Asian cuisine, but somehow my choice to love and bring it into my adult life makes it even more special to me now.

Veronica and Alex

To this day, my parents don’t and can’t understand my or my sister’s experiences, both good and bad, of being minority women. However, I can say confidently that everyone understands what it’s like to be different. As an adult, I thank my parents for doing such a good job at teaching me how to embrace differences in the face of those who try to put me in a box. As hard as they tried, my parents couldn’t keep me from struggling to find my own identity, but now I know that it’s up to me to make those decisions in life based on who I am as an Asian-American woman and who I want to be.

Written by Alex Romero

Guest Writer

Some background on me

A year ago, I graduated from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro with two degrees in French and Francophone Studies and Art History, and I’ve spent this past year in France teaching English at the secondary school level. I’m currently back in the States as I prepare to start graduate school in the fall at the University of Denver studying International Development. I hope to pursue research geared towards creating educational systems that are inclusive to women and subsequently help aid women’s political and social advancement in developing nations. My hobbies include cooking, knitting, and language learning.